Joe Milloy, POW Life

LIFE IN THE BULGARIAN PRISONER OF WAR CAMP IN THE WORLD WAR II

Bulgaria in the WW II as in the WW I was on the German side. Their military forces were fully mobilized throughout the entire war but did not actively participate in fighting. At the end of the war, under the pressure by the Soviets, Bulgarian Army fought the retreating German forces in the Northeastern Yugoslavia. However, Bulgarians did help German forces by occupying parts of Serbia and Greece. They, also, annexed Macedonia and Thrace. Also, Germans used free Bulgarian roads and railroads. The only German military forces, mostly Air Force, were stationed around main transportation hubs like Sofia, Plovdiv and few others.

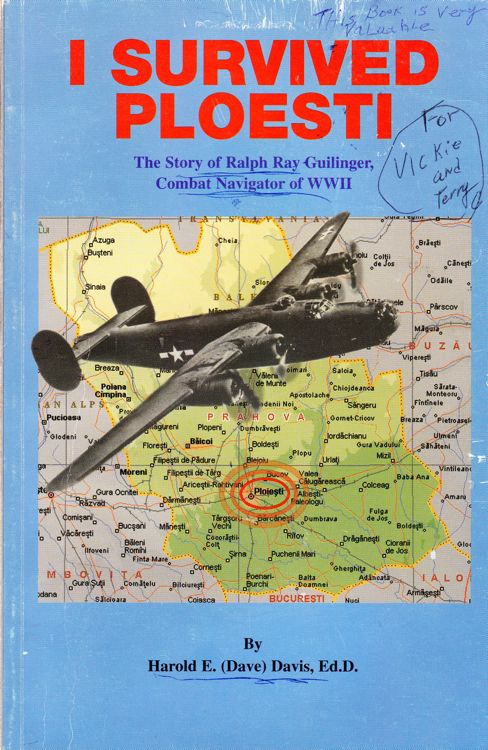

The POWs in Bulgaria were mainly American airmen shot down over the targets in Bulgaria, or who bailed out over the Bulgarian controlled territory, while returning from the missions against Rumanian oil fields. There were also a few British flyers, mostly Australians and South Africans. Also a "commando" British major, a Greek private, from the major's outfit and two Dutch civilians, who claimed to be brothers, members of the Dutch underground, working for British. They were caught while attempting to cross the border into Turkey. Among the American paws there was a black lieutenant, pilot of P-51 "Mustang". He was a quiet but very friendly person. There were, also, three American natives: a P-38 pilot from Oklahoma. His face was seriously burned. Two others were sergeants, gunners of which one was, I believe, an Aleutian with very pronounced features of his race. He was a great attraction for Bulgarian solders.

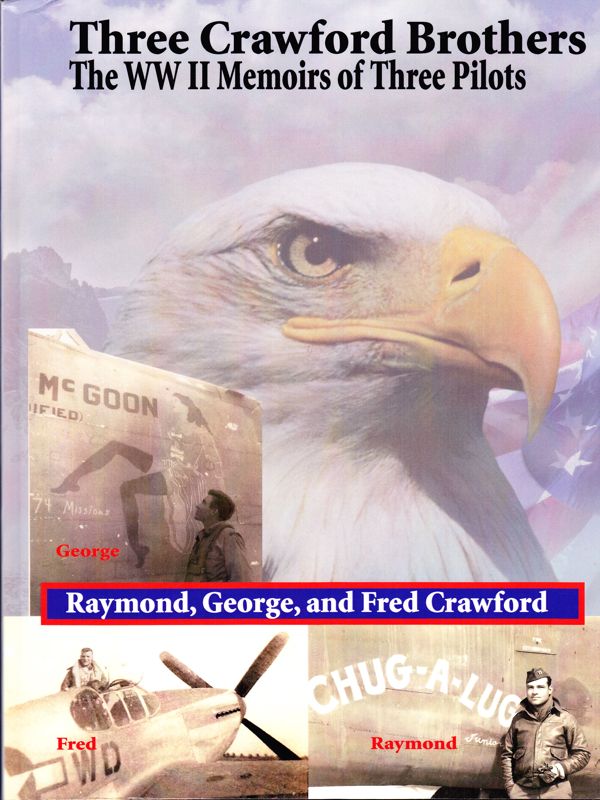

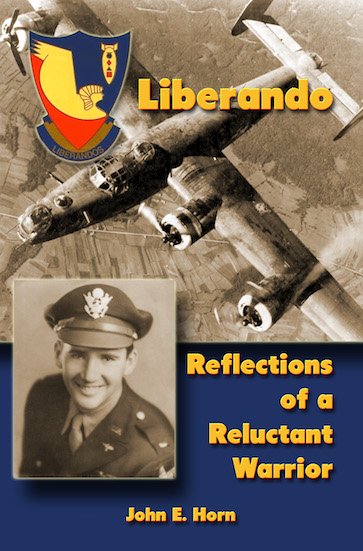

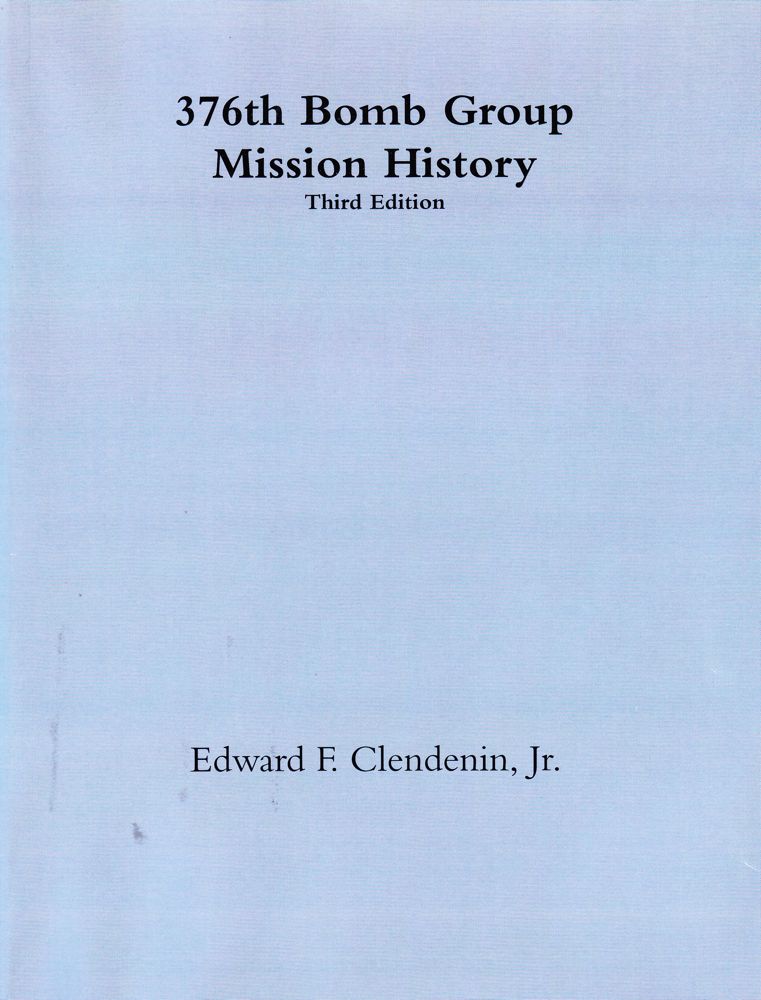

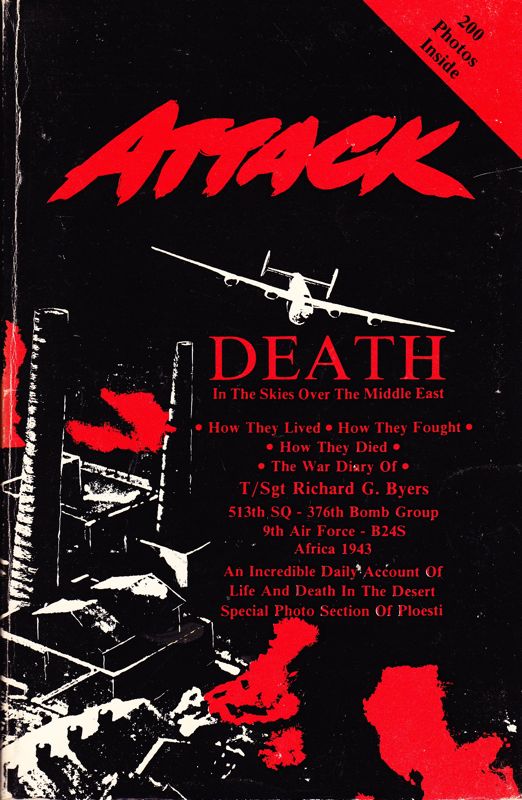

My crew from 512th Sq. 376th Bomb. Group, 15th AAF in Italy, was shot down November 24, 1943, by a Messerschmitt, upon leaving the target, the marshalling yard in Sofia. We bailed out some twenty minutes later over a small village, Bogumila, Macedonia. After six or seven days and several jails we were brought to Sofia POW holding compound. There we found thirteen other American paws. They were survivors of five B-17s and B-24s crews who bailed out or crash-landed in Bulgaria, returning from the August 1, 1943 Ploesti air raid. Two of them had each lost a leg and they were hobbling on improvised crutches. Some were badly burned.

Day or two later the Bulgarians brought in Lt. Philip Gore (from Panama City, FLA), from 514th sq., 376th B.G. with seven members of his crew. They were shot down during the same mission as ours and have bailed over the country side near Sofia. After the regrouping on the ground, and while walking through the field, they were ambushed by the local militia. The Bulgarians fired five shots killing the crew's bombardier and one gunner. The radio man was hit by three bullets wounding him in the armpit and the left heel. The third bullet went through his field hat causing him no harm.

The life in Bulgarian captivity was very difficult.

The few weeks we have spent in the Sofia military prison were not too bad. The treatment was fair and the food, regular Bulgarian military diet of bread and bean soup, was adequate. My injured back was very painful and I was taken by an ambulance to the military hospital in Sofia. At the hospital, doctors admired my brand new, tropical worsted green uniform, shirt and pants. However, for my injured and painful back, doctor shrugged his shoulders and after a brief consultation with the officer who brought me in, I was told that there was not much he could do for me. While my back did heal, it remains painful to this day.

During those days in Sofia, we had many visitors: both men and women, all curious to see Americans. One day a Bulgarian who said he was before the war a Chrysler representative in Bulgaria visited us. He spoke fairly good English. With permission of the authorities, he brought to each one of us a pair of Bulgarian military underwear, a towel, a small toothpaste with a toothbrush, a Gillette razor blade with some razors and plenty of cigarettes. Since it was December and very cold with no heat, The Bulgarian military gave us some old and worn out military uniforms and a blanket for each one. This was the only time they gave anything to the POWs. The stuff, few of us got while in Sofia, served later on as communal property; we shared everything.

Our real hardship began when, early in January 1944, we were moved out of Sofia. They told us that they had to protect us from our own bombs. It is true that while we were in Sofia we endured a couple of daylight air raids. Some bombs fell close enough to rattle our doors and windows.

Our new camp was clear across the country near the town of Shuman (now Kolarovgrad) in the eastern Bulgaria. The camp was an improvised arrangement, located on the top of a small hill. It consisted of a single, one story structure with two larger rooms and a basement. The kitchen was in the basement. It had, also, space for wooden tables and benches where we ate. There was, also, a newly built small building that served as the guard house. Our building was intended and used only during the summer and had no heating of any kind. Washing and toilet facilities were non-existing. The door and all windows had heavy iron bars. The iron gate was most of the time locked with a huge padlock - probably dating back to the last century.

Although the building was located in the middle of nowhere and with open space all around, Bulgarians left a very small yard encircled with two rows of concertina barbed wire and a row of barb wire in between. In addition they had a large, mean looking dog, "Murdja", tied to a leash which was able to slide on a tightly stretched cable. Apparently unhappy with this arrangement, Murdja barked day and night. Our toilet was a field latrine type a trench about two feet deep, two feet wide and ten feet long - with no privacy or shelter from wind or rain.

All of the prisoners, about thirty-seven of us (we had some P-38 pilots picked up in Bulgaria) were housed in one room. Because of the newly arriving prisoners, we had to rearrange our sleeping accommodations. We drew straws and about one third of us had to sleep on the floor on some worn out mattresses filled with chaff. Mice, bedbugs and lice were part of our daily life and entertainment. With any group of new arriving prisoners, we would get a batch of new lice they picked up while passing through the prisons in various parts of Bulgaria.

For some unexplained reasons, the Bulgarian Military declared us to be political instead of military prisoners. This classification entitled us to only one third of a solder's ration. Our meager rations were handed over to Bulgarian military cooks to prepare our meals, which consisted of a small, thin, and frequently moldy piece of bread and a ladleful of watery bean soup with no beans in it. In spite of the fact that our bread ration was small, the Bulgarian cooks were stealing some of it in order to trade for whatever we had that could be exchanged for some bread. Although Bulgarian authorities took away from us anything that they considered to be property of the U.S. Government, they seldom took our "G.I." Waltham wrist watches. One watch would bring between one and one-and-a half loaf of dark, hard, moldy Bulgarian military bread. We were hungry all the time and all we talked about was food. Everyone has made a special menu for the day we get out of the camp.

As all good POWs, we dreamed and planned our escapes. We divided into small groups, each having a Yugoslav for language purpose. Although the Serbo-Croation language is not identical to Bulgarian, it is close enough to get along without a great difficulty. In spite of our meager rations, each one of us saved a few bread crusts for our escape. We hid those crusts into our improvised pillows. But sleeping on the floor, it provided a field day for mice. During the night and sometimes during the day, mice ran allover the place. In the night they even ran over our faces. We complained about the mice situation to the Camp Commandant. He listened for while than he shrugged his shoulders and walked away. A sympathetic guard brought us a mousetrap. It was not a problem of catching a mouse, but what we could do with it once we caught it? The only thing we could do was to take mouse outside in the yard, let it go and wait for it to come back.

We did have one escape attempt. We studied every inch of the fence and we discovered a spot that could be worked out in a hole large enough to wriggle through. It was also located far away of the guardhouse. Lt. Joe Quigley, a navigator, and three F-38 pilots decided to give it a try. The advisory committee suggested that they await for a better opportunity, however, they decided to go. It was right after the "D-Day" and the camp atmosphere was rather lax. We had more freedom and more time in the yard. The Bulgarians, always, had at least two armed guards in the yard and around the building. Frequently, the guards would get together and talk or tell the stories. During such an occasion our four escapees sneaked out toward the escape hole. The rest of us were in our room. Three of the escapees made it through the hole but the forth one got entangled in the barb-wire. Murdja, the dog, smelled something and began to bark. This drew attention of the guards and one fired his rifle. Although, we did not see anything, we heard many rifle shots and exploding grenades somewhere outside of the camp. Our iron gate was immediately padlocked and they doubled the guards. The Camp Commander came running and waving his pistol. After about fifteen minutes, the escapees were returned to the camp with the hands tied behind their backs. They were placed somewhere in the attic and put on the "bread and water diet". After seven days they were released and returned to our room. All was forgotten but for a while the situation in the camp was quite tense.

The winter of 1943-44 was very cold and with a lot of snow. Since our camp was on the top of a hill there was nothing around to break the wind. For the heat Bulgarians provided a large pot-belly type stove which required breaking a window pane to accommodate the flue pipe; but there was no wood to keep fire going. The wood they would bring to the camp was used for the guard house and the kitchen. We were given a few knotty stumps, but we had no tools to break them. The few pieces of wood we could chip off, would hardly provide enough heat for our large room with many drafty windows. The only clothing that many of our men had were the electric heating suits and boots. These worked very nicely in the airplane, but there was no place to plug them in at the Bulgarian POW camp. As a matter of fact there was no electricity in the camp at all. The Camp Commandant and the guard house used kerosene lamps.

There was no telephone in camp nor even a defined road between the camp and the nearest town. The guards would walk on foot, close to three miles, to and from their barracks in town. Provisions and wood were brought twice a week by a horse-drawn wagon. We had no books, newspapers, nor any reading material. Solders were forbidden to talk to us. Occasionally some sympathetic solder, usually, while escorting us to the latrine would provide some news or maybe a piece of Bulgarian newspaper. Sometimes we would find pieces of the newspapers in the latrine left by solders or the Commandant. We would bring them to our room and try to figure out what was going on in the outside word.

Since we had no lights, as soon as it would get dark, between four and five p.m., the guard would open the iron gate and yell for "last call" to latrine. Usually there were no takers. That winter we had several feet of snow and the path to the latrine was virtually a tunnel. Going to the latrine meant a long walk in the cold darkness, being escorted by a guard with a bayonet fixed on his rifle. The guard was cold too, and he would keep yelling "berzay, berzay" - meaning "hurry up, hurry up". For the overnight use we had a pail in our room. Needless to say, shortly after the gate was padlocked, the pail was full. For the remainder of the night, the overflow kept spilling on the floor. Some of it the wooden floor would absorb, some of it went through the crevices to the basement bellow, and the rest spread through the room, on the floor where some of us slept.

When we had something to trade for bread, it was done around the latrine. The solders were very careful I not to be seen by the Sergeant or the Camp Commandant. Once the Commandant caught a guard talking to a POW in a friendly manner. He became so irate that he beat the guard about the face with his fists, making his face very bloody. The guard just stood there with a loaded rifle on his shoulder and took all the beating.

In regard to health, we were relatively all right.

There was no one to complain anyway. The occasional sniffles we did let run their course. No Bulgarian doctor or even a medic set foot in our camp at any time. Our youth, our deep conviction that our side is right, that we shall win, and our hopes that our predicament is only temporary, kept our spirits as well as our health, high. However, some newly arriving prisoners would come with bad cases of dysentery or other stomach or like problems. The poor fellows were pitiful as they coped with their problems. Sometimes they were not able to make it out of the building and much less to the latrine.

The condition of a prisoner arriving to the camp depended on how and where he was captured. The lucky ones captured by the military, German or Bulgarian, would be treated to some degree humanely and with some military courtesy. The ones that would get in the hands of the regular Bulgarian police, would probably encounter rougher time, being cursed, spat on, spend time in cold jails but would survive. Those unlucky ones who found themselves in the open countryside or in the mountains and were later picked up by peasants or village police or even militia, would experience very hard time and may have not survived at all.

Lt. Gore and his crew were ambushed and fired upon.

Two crew members were killed and one badly wounded. The survivors were ordered to spend the night in a log cabin. Prior to letting them into the cabin, Bulgarian ordered them to take off there shoes. In the morning their shoes were gone with everything else Bulgarians cold get off them. When they arrived at the camp, they were barefoot. Many other POWs had similar experience. Some prisoners told of seeing other crew coming down in their parachutes but they newer showed up in our camp. Yet, in the WW II, Bulgarians had only one "known"

POW camp.

Prior to each flight, operational personnel would issue to us two small packages: one contained a map of the area we would fly over, a piece of hard chocolate, often "green", and some escape paraphernalia. The other package contained forty-eight "gold seal" US dollars. Word spread quickly throughout Bulgaria that American flyers had a lot of money on them. With Bulgarians shouting first and asking questions later, some downed flyers may have been killed because of these dollars.

Personal hygiene was whatever each individual POW made of it to be. We had no soap. They never gave us any and no place else to get it. The water was always cold and never in an abundant supply. In the first, the "Windy Hill" Camp, as we referred to, the source of water was a pipe in the rear of the building with running spring water. Sometimes there was plenty of it and sometimes it only dripped. In the second camp, water was brought in wooden barrels drawn by mules. Frequently, we had hardly enough water to drink let alone for personal hygiene.

. During the entire stay as POWs in Bulgaria, we had two baths. The first, sometime in July 1944, during a daytime downpour, they let us out in the yard and we ran naked, enjoying the rain and trying to wash ourselves. The second bath was more memorable and the only pleasant experience of our sojourn in Bulgaria. At the end of August 1944, we were taken by military trucks to the town's Turkish bathhouse, known as "amman". At the bathhouse, there was plenty of steam, hot water and towels. We were, even not rushed! We had a great time. Outside of the bathhouse, we were even free to buy some sweets from the street vendors.

We had no particular disciplinary problems in the camp. Beside two "rumored" beatings of prisoners by Sergeant or Commandant, and one attempted escape, Bulgarians never bothered us much. We never had a roll call or any kind of formation. The Bulgarians never bothered to appoint anyone of us as the commander of POWs nor to find out who is a senior man to represent us. From the very beginning, Lt. Darlington was the unofficial spokesman. When we had any complain, Lt. Darlington, accompanied by Lt. Lakich, who spoke a passable Bulgarian language, would ask to see the Commandant. When the Camp Commandant had something to say, usually concerning logistics matters, he would tell it to his Sergeant who in turn would pass it to Lt. Lakich who would relay the message to the rest of us.

The relationship amongst prisoners was beyond any reproach. Although, by the end of our captivity, there were a few hundreds of us and too crowded, we tolerated the situation well. Newly arriving prisoners were met and greeted by the welcoming committee who would try to help them with their immediate needs and problems, including dysentery, lice, and their sleeping accommodations. The Bulgarians would normally bring them inside the camp and dump them. They have done their share!

The interrogations in respect to military intelligence were not very serious. As much as it was, it was done while we were in Sofia. While passing through the prisons, the individual paws were questioned but not really interrogated.

While in Sofia prison, our crew was interrogated by German officers through a Bulgarian interpreter. None of us was questioned more then fifteen minutes. During my questioning, since I understood both the question and the translation of my answer, I was under impression that the interpreter was giving to the German officer what he understood or what he believed would please the German. My interrogation was very brief and it ended with an offhand slap on my face. Others complained of a similar treatment.

Sometime in April 1944, a representative of the International Red Cross came to visit our camp. He was a tall Swiss fellow with a heavy German accent. In response to our complain that we were not permitted to send messages or receive any mail or packages, he replied that the American planes were bombing trains and therefore no mail or packages could get through. Dr. Joseph Goebels could not have said better! He left and that was that: no mail, no packages. Some prisoners spent fourteen months in Bulgarian captivity without a single letter or a package.

In May 1944, we were "honored" by another visit. This time it was a Bulgarian two star general. I presume he was the Regional Commander. He spoke a very good French and one of the paws, Lt. Thomas Judd, formerly an exchange student in France, got into a heated argument with the General. He told him that the Bulgarians were violating the provisions of the Geneva convention. The General yelled back that the Americans were behaving like barbarians bombing women, children and cemeteries. Nevertheless, the General promised to look into the matter.

A week or ten days later, we began to receive full military ration of bread a day and a few visible beans in our soup. They also gave us some money, our pay corresponding to our ranks. This pay bonanza lasted for two months and then suddenly stopped just as it came - without any explanation. However, it was good as long as it lasted.

A vendor was allowed to come to the camp and sell us items of the rationed food: beans, onions, eggs, cooking oil, and occasionally, he would smuggle in for good money, a bottle of some cheep Bulgarian brandy. It was a middle of summer, the weather was nice, the food became adequate and the news from the outside, as much as it could filtrate in, were good. Our lives suddenly became bearable. Some brave guards would occasionally bring a local newspaper for which we would pay one hundred leva versus two leva - newsstand cost. News about the German "strategic" withdrawals and regroupings were sure indication of their nearing defeat. It would be only question of time. The new prisoners would bring us news too, sometimes even from our own units.

The D-Day made it clear to Bulgarians that Germany was losing the war. Their attitude toward us did not change that much, but it became somehow less oppressive. We were just looking at each other.

By the end of July 1944, our "Windy Hill" Camp became overcrowded and we were moved to a new camp, about four hour walk from where we were. The new camp was on the same mountain ridge. It was also an improvised arrangement: a larger two story farm house, with cots for all of us and a much larger yard. Unfortunately, the influx of new prisoners forced some newcomers to sleep on the floor or wherever they could squeeze themselves. The weather was nice and the feeling that it will not be for long - made it bearable.

On September 4, 1944, Bulgaria declared neutrality.

Two days later, on September 6, Bulgaria declared the war on Germany and the Germans responded by bombing Sofia. In the same time, the Soviet forces were entering Bulgaria from Romania and were approaching Shuman and our camp. On September 7, under the cover of darkness, we were loaded into trucks, taken to the railroad station, put on a special train, guarded by a military escort and we headed west toward Sofia. While passing through the town, we observed Soviet military vehicles parked on the streets and around taverns. The following morning, half way to Sofia, we stopped in a small town, Lovech, and were told that since Germans were bombing Sofia we would have to change our route and head toward the Turkish border. Around midnight of that day we pulled out and at noontime the following day we arrived in Stara Zagora, a small town in southern Bulgaria. There we were caught in the Bulgarian revolution.

Nobody knew what was going on. Bulgarian officer in charge of our military escort, complained that we ran out of food and he did not know where to get more. In the evening, several of us went into town to find something to eat and a place to spend the night. Near the center of the town, we were intercepted by a communist (partisan) "liberation" patrol. A young civilian in a shirt with rolled up sleeves and a gun in his hand, was accompanied by several armed men - military, militia, and civilians. When the leader learned that we are Americans and ex-POWs, he promised to find us food and shelter. We went along with the patrol watching them knocking on certain houses, arresting people, mostly in their sleepwear. One of the patrol member would tie them and take them somewhere. The new armed solders or civilians would join the patrol. After about three hours of this and no food, I explained to the leader that we should return to the station. He agreed and let us go. We spent the rest of the night hungry, cold, sleeping on the ground outside of the station.

The next morning, the Bulgarian officer and I went back to the town to look for food. It was Sunday and the town was very quiet. While drinking some coffee, we noticed smaller groups assembling here and there. He explained, those men were "shumkari", men who belonged to the "underground".

Late that afternoon, the Orient Express train stopped at the station and our railroad cars were attached to it. By the noon next day we arrived at the Turkish border. After three or four hours of checking, counting, and recounting, the Turks let us in and we arrived at the town of Edirne. There, we were met by the American Counsel from Istanbul. We were not anymore paws.

We arrived in Istanbul the following day. We spent three days aboard several boats resting and recuperating from our ordeal. We received new Turkish uniforms and American military shoes. The Red Cross representatives came and gave us small shopping bags with useless trinkets. From Istanbul we proceeded by train to Aleppo, Syria, where we were loaded on C-46 and flown to Cairo, Egypt. In Cairo, we were given a shower, American uniforms and shoes. After a quick medical check up, we were flown by B-24s back to our units in Italy. We were back in San Pancrazio.

Immediately upon return to Italy, several former POWs in Bulgaria, including Lt. Col. Smith of 376th B.G., and Lt. Thomas Judd, were flown back to Bulgaria to search for the military and civilian authorities, who have mistreated prisoners. In 1951, I met in Athens, Greece, former Lt. Judd who at that time was the Third Secretary of the US Embassy. He told me about his return to Bulgaria. Their mission was not very successful. The country was in a total disorder. All of the military were on the front fighting retreating Germans. The new communist authorities did not know anything about anything. However, he heard that our last Camp Commander, one accused of beating prisoners, committed suicide while others just vanished.

Joe T. Milloy

(Zivko T. Milojkovic)

Former POW in Bulgaria, from Nov. 1943 through Sept. 1944

January 1992

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to read about the reunion details.