Dean Holman, Mission February 23, 1944

Personal Recollections of Dean O. Holman

Writing of this account begun November 22, 1988

Typed on word processor by Cary Holman April 1995

Edited July 1997

Read more about Dean Holman's earlier experience as a prisoner-of-war.

(The spellings of names and places in this account may not be correct, despite our best efforts.)

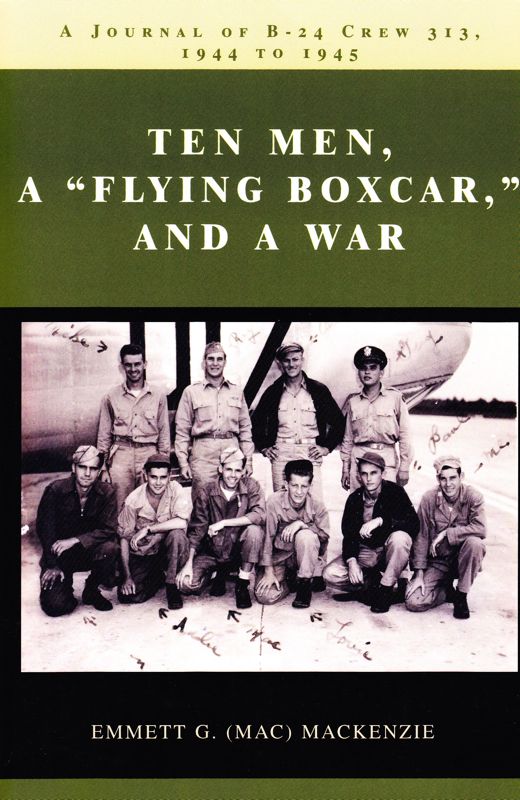

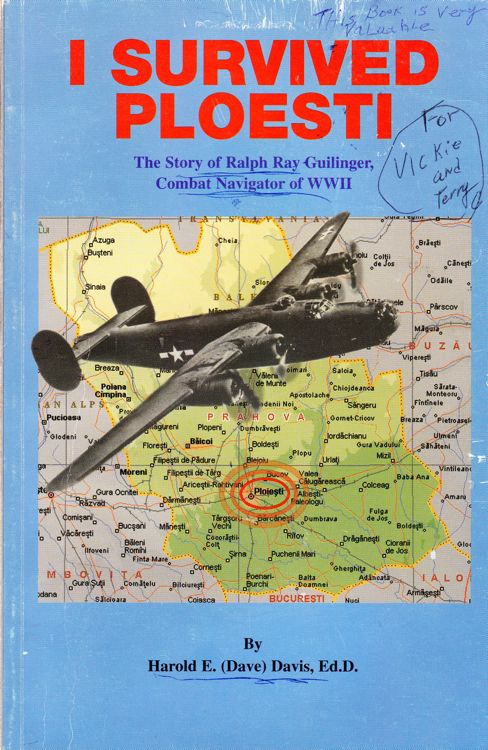

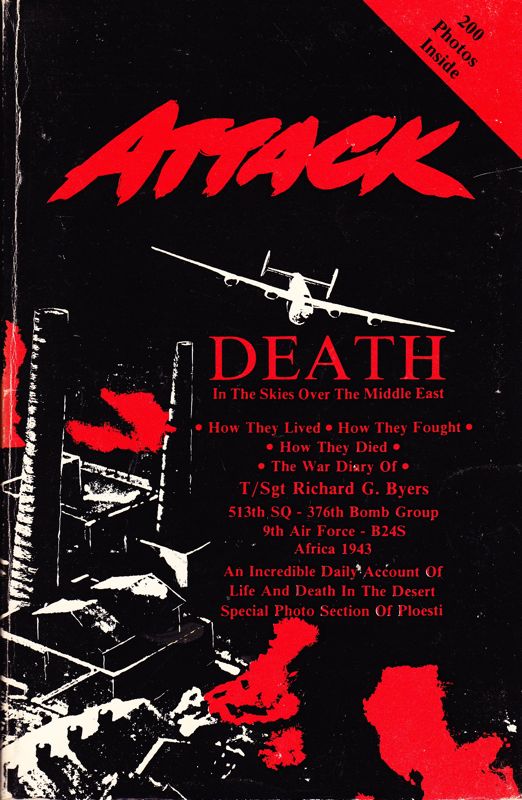

I was part of the 376th Bomb Group stationed near Brindisi, Italy . The morning of February 23, 1944 , our B-24 Liberator Bomber crew was not supposed to fly. The day before our pilot, Lieutenant Eugene Thurman, had gotten his feet frostbitten when the heater in the cockpit failed. But at 4:00 AM they woke me to say I was going with another crew that was also part of our 376th Bomb Group. One of their crew had too much to drink the night before and was sick. It was the first time I had flown with another crew. I had only met the tail gunner. This was my thirteenth mission.

Some of the enlisted men said that I would be flying in the nose turret. The man in the nose turret was shut in by the navigator. I understand there was no handle to the door on the inside of the turret. Space was very tight. The nose turret gunner's parachute was on the outside of the turret. So he had to rely on the navigator or bombardier to open the door so he could get out in case of an emergency. I refused to fly in that position because I had never flown in combat with the navigator nor bombardier on this crew. So this day I flew as one of the two waist gunners.

Our target for our bombing group that morning was a ball bearing factory in Steyr , Austria . Usually we were to be over our target close to noon so that any anti-aircraft had to shoot into the sun. The 8th Air Force from England was to hit targets in another area in Germany that would spread out the German fighters. But the 8th Air Force could not take off because of bad weather. Also, a group of B-17s at Naples , Italy , was grounded. So our two groups of B-24s was all the Germans had to shoot at.

We encountered Messerschmitt 109 fighter planes, known as Goring Yellow Noses because they painted the nose cone yellow. They were the top pilots of the German Air Force at that time. I don't think there was any ground fire. I saw no smoke that follows when anti-aircraft shells explode. And, it would be unlikely that they would shoot into the air when their own fighters were also flying there.

Before our plane was hit there was so many men bailing out of other damaged planes that we could not report them all. When our plane was hit I knew I was hit in the left leg. When I got up I could not stand on it. When I got back up I fired at one of the German planes while standing on one leg. It was probably out of range. This was the only time I ever fired at an enemy plane.

The Messerschmitts carried a 9 mm cannon and a 50 calibre machine gun. My ankle wound could have been from a 50 calibre machine gun. But it was probably from a cannon shell exploding because I also had shrapnel wounds in my back, stomach, shoulder, right leg, and buttocks. I even have little tiny pieces of shrapnel in my right hand that were never removed.

We could see the plane was on fire, and the intercom to the men in front of the plane was out. We started to get our parachutes on. We wore a harness but had to attach the chest parachute to the harness when we were ready to use it. There were four men stationed in the back of the plane. A hole for the purpose of bailing out was on the floor of the plane. The first man ready to jump sat down at the hole with his feet out the hole, but did not jump. So the next guy who was ready pushed him out.

I had trouble with my parachute because a first aid kit had slipped down where the snap was to go. All of the other three men stationed at the back of the plane had jumped by the time I was ready. Some one had told me to be on your back when you pulled the rip cord. So I leaned back and it worked--you could get on your back. I didn't think it would work. The reason was to keep your face from getting cut up by the shroud lines. It didn't feel like I was going down.

A German plane flew close to me and we waved at each other while I was still in the air. There wasn't much else I could do. As I fell I had the sensation that I was going up--not down--until I could see the ground. It didn't take long after you could once see the ground to land. When I pulled up my injured leg I probably had my right leg pulled up too. So I made a good landing because you were supposed to land with your knees bent. I remember there was snow on the ground.

After I landed in a field near a farm house a small plane flew over me. We had an escape kit which had some small chocolate squares each equal to a meal. I was hungry so I ate several of the squares.

There were four men and a woman down the hill near the farm house. I was more afraid of what the women might do to me than the men. There were stories where women had attacked airmen who had parachuted after or during a bombing. Some women would take the opportunity to attack those who had been dropping bombs on their home. Not all the bombs always hit the military target. Soon the men came up to where I was. They had an old rifle. We carried a 45 pistol in a shoulder holster which put the gun over our heart. They didn't know how to release the holster. It was held by a snap that I was laying on. I reached over to unfasten it. They all moved back from me. I always wondered if they had any shells in their gun. They made no attempt to point it at me.

They carried me down the hill to the house and laid me on the floor. It was not long until a German soldier came. I was wearing an electric flight suit. It was hard on the lady's scissors to cut through the wire in my suit to get to my leg wound. I was getting cold. The lady gave me a very small amount of something to drink. I don't know what it was, but as soon as I swallowed it I was warm from the inside out. There was an American lieutenant at the house. He was telling the lady in English about his daughter, and was showing her the daughter's picture. We weren't supposed to have a picture of our family, or any thing except our dog tags. Anything could provide the enemy with information they could find valuable. Later I found out he was the navigator on the same plane I had been on from my description of him to Morris Ruttenburg, who was the tail gunner and regular crew member on that plane.

They put the lieutenant and me in a bobsled and took us down a hill to the main road to an ambulance. That is the last time I ever saw that lieutenant. I do not know whether the lieutenant also got in the ambulance with me or not. I don't remember much until I woke up the next morning in the room other than it was dark when we got to the hospital, which was a hospital for members of the German Air Force in Wels, Austria .

There were three other Americans in the room with me. Their names were Morris Ruttenburg, Joe Fritche, and Lieutenant Kendall Mork. In the bed next to me was the tail gunner from the crew I was flying with when we were shot down, Morris Ruttenburg. He had a wound similar to mine in his right ankle. On the other side of Ruttenburg was Fritche who had similar wounds but in both ankles. I don't remember what was wrong with Lieutenant Mork, but he could get out of bed, so he must have not had leg wounds. We were not out of these beds for the next thirteen weeks when the hospital was bombed.

There was an English-speaking German nurse in the hospital. She told us that they had taken our dog tags and told the Red Cross that we were alive and prisoners of war. But apparently that message did not get through. The doctor who treated me was Dr. Mooseman, who was an Austrian professor of medicine from Vienna before entering service as a Major in the German Army. The English-speaking nurse was always the nurse with Dr. Mooseman. The only English I ever heard Dr. Mooseman use was "move toes."

Five days after I got to the hospital my leg began to swell in the cast. Dr. Mooseman was gone so they did not do much about it. When the doctor returned he cut a hole in the cast and started treating the wound with powdered sulfa. He said it was gangrene and if he could not stop it in 24 hours he would amputate before infection reached my knee. The sulfa did not stop the gangrene. On March 1 they took me to surgery. They were not sure if they would amputate below or above the knee. I've always wondered if an American doctor would have taken the chance to save my knee with the infection that close to my knee. They took my leg off six inches below my knee, left it open (they called it a guillotine amputation), and put four drains in it. I've always been thankful that Dr. Mooseman saved my knee. About a month later the doctors told me they thought it would be all right.

When I woke up from the amputation surgery an Austrian girl was sitting by my bed. She was not dressed as a nurse. The other fellows said that she had been there ever since I returned from surgery. She told us that her brother was a prisoner of war of the United States . We assured her that he was being well treated. She left shortly after I came to. I never saw her again.

They fed me white rolls with jam. I ate it for several days or a week. One day I asked for more. I never got white rolls and jam again. I was back to the black bread and lard like all the other prisoners. We offered the lard to a nurse. She refused out of fear that she would be reported if she was discovered to have accepted it.

They elevated my leg on a ramp about eight inches high. The ramp was a smaller version like the ones we use to drive a car up on. My leg was elevated on the ramp for the next three months.

My wound was dressed about every other day for a long time. Within two weeks after the surgery while they were dressing the wound one of the drains came out my leg. The doctor came to replace it. He thought it would be a simple procedure. One nurse held my leg. Another (large) nurse laid across my chest to keep me from moving by holding the opposite side of the bed. The doctor then replaced the drain. The pain was terrible. I screamed and hollered but the nurse was successful in holding me still. That was the only time that I was hurt. Later the doctor apologized. He said that if he had known it would be that painful he would have taken me back into surgery to do it.

One time when two nurses were changing my bed they were talking and laughing in Austrian. I laughed with them. One of the nurses slapped me up the side of my head. She really jarred me. I never knew what they had been laughing about--and neither did any of the other prisoners--but apparently I wasn't supposed to laugh. Then they just went on changing the bed.

After about two or two and a half months I thought I could get out of bed. When I dropped my wounded leg over the side of the bed I almost passed out from the pain and fell back onto the bed. None of us prisoners told the hospital personnel about the incident. I never tried it again.

It probably would have been longer but at about noon on Decoration Day 1944 the Americans bombed the hospital. We later heard that the Allied Air Force knew of our being in this hospital, but considered us expendable. This holiday in late May was called Decoration Day because on this day people decorated graves of loved ones, including but not limited to those of veterans. Now this holiday is called Memorial Day by most people, but I still call it Decoration Day.

This hospital was a tar paper barracks type of building. The bombs that were dropped were fragmentation and incinderary type. The hospital caught on fire as a result of the bombing and was destroyed. The bombing run was five waves with two or three minutes between each wave. After one wave only the bottom of a water bottle remained on a stand by my bed a few inches higher than my head. After another wave passed there was a row of holes a half-inch in diameter in the wall a few inches above my mattress. I looked to see if I had been hit. I was not. They must have come from an angle above. After one of the waves the Lieutenant said that we had better start praying. I told him that if he was just now starting he was about two waves behind.

There were eleven other Americans in the hospital with me at the time, four of us in each of three rooms. All but one German patient, who was too badly injured to be moved, were taken to an air raid shelter. Two Americans were killed in this bombing attack, and one officer received a very bad leg injury from the bombing. No one in our room was injured seriously during the bombing. Fritche, however, did receive a minor wound.

The air raid siren sounded often to warn of approaching enemy aircraft. But for as long as we had been there none of our planes had dropped any bombs when they flew over. So many of the local people never bothered to take shelter during this air raid. A lot of local people were injured because they were slow to take shelter.

After the bombing stopped a nurse carried me out of the hospital piggy-back. This time when my injured leg hung down I did not feel any pain. She handed me down to a man on the street below who took me across the street to a larger, permanent hospital. They put me back in the corner of a room full of Germans--I guess they were Germans because I couldn't understand what they were saying. I kept my mouth shut because at first some thought I was part of the bombing raid.

The next day they took the 10 remaining Americans to the second floor of a school house in a small village nearby. We were brought food from somewhere in the village. One day the girl who brought us our food brought cans of peaches for two of the more seriously injured prisoners. None of us ever got peaches. They were a real treat. A guard walked in while she was giving the prisoners this special treat. The guard asked the girl to leave. She never brought food to us again but we did see her later in the street from the window.

We could look out the window and see the kids coming to school to the floor below. As the kids walked by a particular man on the sidewalk each day they gave the "Heil Hitler" salute. He may have been the principal or a teacher. The room we were in had a picture on the wall of Hitler. The guards were seldom in the room with us except to check on us about once a day. After the guards left we would turn the picture of Hitler so it faced the wall. When the guards returned they would turn it back around. The guards never said anything to us.

We were there from four to six weeks. Dr. Mooseman continued to be our doctor. He had received orders that we were to be moved. On June 30, 1944, we were sent by train to a prison hospital at stalag 9C at Obermassfeld , Germany . The train had wooden seats. I had been either in or on a bed for the last four months, so the seats seemed very hard. There was one row of potatoes along the train tracks that seemed to go on for miles. On the way we passed through a German interrogation center. The German interrogator spoke perfect English. We had been in the hospital for the last four months, so we weren't expecting to be interrogated. During the interrogation they took all the names and addresses we had of the German army doctors and two nurses who took care of us. I've often wanted to write them. I sure wish I had their addresses. The interrogator left a notebook on my bed when he left the room. When I looked at it it had listed many Americans in different crews. Not all the listings of the crews were complete. Later he returned and took the notebook.

A few weeks later, on July 26, my folks found out I was a prisoner of war. Up until that time I was just missing in action. I assume that the news of my status had to do with the interrogation. They announced at the Farmer City Fair that Dad had received a telegram. Dad picked it up at the depot and my family then found out that I was a prisoner of war. It was announced at the Fair.

At the hospital at Obermassfeld the doctors were Australian and English doctors, many who had been prisoners for a long time. They worked under the supervision of German doctors. The only officers we ever saw were these doctors. They did not live with us. All of us that lived together were enlisted men.

We spent all our time in one very large room at the hospital in Obermassfeld. The one room held 50 or 60 people, maybe more, from 6 or 7 countries. We were put in groups of 5 or 6 prisoners to prepare our meal. We called each group a combine. I don't remember why. Each combine prepared one meal each day in a small bread pan. The Germans furnished us potatoes and black bread pretty often. We also could withdraw some items from our Red Cross parcels to combine with the potatoes. They would heat the meal we prepared in this one pan once a day. I don't remember what we ate the rest of the time.

The Red Cross parcels were held by the Germans. They were intended to last for a month. We could check out items from our parcels as often as once a day. If we checked out a canned item the can was punctured so that you couldn't save it for escape purposes. The parcels often contained salmon, sardines, cigarettes, candy bars, crackers, and raisins. The cigarettes and chocolate bars had the highest trading value. At the time I did not smoke so I traded my cigarettes mostly for candy which I could eat between meals. When a guard was alone sometimes he would trade us for seasonal vegetables such as tomatoes or onions to add variety to our meal. The trades almost always occurred in the latrine. That's the only time a guard could be pretty sure no other German would oversee the trade.

There wasn't much to do. We did have heated discussions about whose country was doing the most for the war effort. Usually it was the English and the Americans that were the most involved in these discussions.

One American prisoner, Warren Rudolph, whom we called Rudy, would tell ghost stories sometimes at night after the lights were out. He would just make them up as he went along. He could just go on and on with them. The whole group would sit and listen to his stories. One night during a thunderstorm he was telling one of these stories. The man on the top bunk above Warren had a shoulder cast. He rolled over and dropped his arm over the side of the bed at the same time as a lightning flash. It scared Rudy who was telling the story. He let out a big yell. The group kidded him from then on about being scared by his own ghost story.

There was a small room at the end of the large room we all stayed in. We never used that room. One day they carried in an injured Canadian soldier who did not want to live into this small room. They asked some of the prisoners to go in to talk to him. A few tried, including fellow Canadians, but no one had been able to get him to respond in any way. Then Rudy said he would go to talk to him, and that if the soldier still wanted to die when he was through talking to him he ought to die. Rudy talked to him for over an hour and the man responded. A few days later they carried him back to his former quarters. That was the last we ever saw of him. We thought that Rudy just talked him out of dying.

We found other forms of entertainment. We would gather around the bed of someone coming out from under anesthetic to see how they talked and reacted. Sometimes we would have group singing. The guards couldn't understand why we would be singing since we were prisoners of war. Late at night after lights were out once in a while someone would have heard news that we would gather around to hear. Usually the person with the news was an Allied doctor with a secret radio.

My knee was stiff because it was on the ramp for over 3 months after the amputation. One day while walking on crutches the crutches slipped on a wet floor. When I fell I bent that knee back all the way. I passed out from the pain. When I came to my knee would bend normally. It probably saved months of therapy.

The last few weeks at Obermassfeld we were moved from the large room out to some barracks. Any time an air raid siren sounded we were ordered back inside the barracks. The American fighter pilots would fly pretty high over us. Before we went back inside one of the prisoners who was an English man would shake his fist and imply that the American fighter pilots were afraid to come down and strafe the area so he could see them. One time one of the pilots did fly low and strafe the nearby railroad yard. When the gunfire began the English man was one of the first prisoners under a bed. So he missed seeing the American plane.

In this strafing attack some of the Germans were hurt. They asked the prisoners to be blood donors for the injured Germans. I heard that some of the prisoners volunteered. No one that I knew did, but probably no one in the barracks I was in was healthy enough to give blood.

We had been eating black bread since we arrived at Obermassfeld. One day we tried to toast it on the heating stove. The bread caught on fire around the edges, on the crust of the bread. We later heard that the bread was rolled in sawdust. Maybe it was the sawdust that caught on fire. The bread was also very heavy. The guards would carry it in on one arm as you would firewood. When they dropped the loaves on the table it sounded like they had dropped firewood, too. When the guards moved us by train the guards carried briefcases filled with this bread and jam for themselves to eat. It is all I ever saw them eat.

All those prisoners whose names were on the repatriation list were moved by train to another stalag, 4D, at Annaburg , Germany . According to records from Joe Fritche, that was on November 1, 1944 . We were there until January 15, 1945 . There we had better food and better privileges, including access to a library and occasional walks in the woods outside the stalag. We had a good Christmas dinner there. On some of the walks we picked up small limbs to use for a Christmas tree and tin foil thrown out by Allied planes to interfere with German radar. We used that to decorate our rooms for Christmas.

On January 15, 1945, we were put on a train to go to Switzerland for an exchange of prisoners. There were cars on the same train for general German passenger transportation. They carried me through the train station at Frankfurt to change trains. That's where I saw the most damage from Allied bombings.

One time while in a train station the air raid siren sounded. The train pulled out very quick. Just outside of town the train stopped with a large hill on one side of the train and a wooded area on the other. Everyone but the prisoners left the train--guards and all--and went into the woods. When the American planes were gone they all got back on the train and we continued on our way. When we stopped in Switzerland a train loaded with German prisoners of war were on the track a few feet from us headed back to Germany .

We arrived in Switzerland January 20 at 1:00 AM . Throughout our trip all lights had been blacked out. As we approached Switzerland that night it was very noticeable that in Switzerland all the lights were on. The next morning we were allowed off the train for about an hour. But none of us had any money to spend. While here we were each given a bag from the Red Cross containing toilet articles. That bag hung for years at our home on the farm on the back of the bathroom door as a rag bag until it wore out.

From there we went to Marseilles, France . We arrived on January 22. We were put on an American hospital ship, the U.S. Algonquin. That was the first time since I had left Italy on February 23, 1944 , that I had seen the American flag flying. I was put to bed and started other medical treatment. The treatment may have included penicillin, but maybe not. At that time penicillin was a relatively new drug, and may not have been that available. They wouldn't let me out of bed.

According so some records we were put on the American chartered Swedish exchange ship, the Gripsholm, on January 24. But we were in port for a couple of weeks. There were 2 or 3 men to a cabin. We had good food since the Gripsholm was a luxury liner. On the way home on the Gripsholm I received 50 penicillin shots, one every four hours, by a male nurse. He was very good at giving shots. After a few days he didn't even wake me when he gave me the shots while I was sleeping.

On the Gripsholm all prisoners were given $75.00 of their back pay. I had been paid last at the end of January, 1944. I had twelve months of back pay coming. That was the only year I have ever saved 100% of my salary.

They said that they would open the bar on the Gripsholm when we got to sea. If there was any trouble and they had to close the bar it would not be opened the rest of the trip. Apparently there were no problems because it remained open.

My roommate on the Gripsholm, Lloyd Helms, did not come back to the cabin one particular night. About midnight I started looking for him. I found him on the top deck asleep in a deck chair, having had too much to drink. Other people had thrown their blankets over him to keep him warm. He had a leg off, too, and so was on crutches like me. I got him up and back to the room with some difficulty. He still was not sober. I told him the next morning that that was the last time I would come and get him. The next time he could just sleep outside in a chair all night. It never happened again.

We arrived in Staten Island, New York, on February 21, 1945 . All the way across the ocean I was up on crutches. But they wouldn't let us walk off the Gripsholm. I was taken off board the ship on a stretcher. I think the stretchers were just for publicity. We were taken to Halloran General Hospital , in Staten Island . As soon as we arrived at the hospital we were once again allowed to be up on crutches.

There must have been hundreds of wounded prisoners on the Gripsholm. All were processed at this hospital. We could all make one call home as soon as phone lines were available. My folks did not have a phone. I probably called Parrs, Coxes or Nicklauses. Wherever I called it seems that my folks were there and I was able to speak with them. I don't know how I knew where to call or whether their being there was just by accident.

A group of people from the USO came to the hospital and gave a party for all of us on the first Friday night after we got there. Some of the girls invited the three of us at our table to come to a party the next night at a private home in Brooklyn . The other two fellows could not go on Saturday night. One had relatives coming to meet him. I went alone. They told me how to get there by train from the hospital. There were several other servicemen at the party, but I was the only one who had been a prisoner of war. They seemed to think I had been starved and I needed to eat a lot more. The rich food was nearly making me sick because my system was not used to the amount and richness of such food over the past year.

When the party was over there were no more trains running back to the hospital. One of the girls who had invited us, Carol Lukes, took me home with her. She woke up her folks to tell them I was there. The next morning her mother served bacon--which was rationed at that time and very hard to get--and eggs, and offered to try to get me anything I wanted for breakfast. After I was discharged and raising hogs I sent Mr. and Mrs. Lukes an entire side of cured bacon. I stayed at their home most of the day on Sunday. I went back to the hospital that evening, which was 24 hours late on my pass. No one had missed me but those in my room.

From this hospital soldiers were sent to the closest hospital to their home that could treat their wounds. For me that was Percy Jones Hospital in Battle Creek, Michigan. A few days later I was sent to Percy Jones Hospital. The first weekend I was there neighbors from home, Marcus and Pearl Parr, brought Mom and Dad to see me. During that visit Mom told me that they had received news that five of my original crew had been killed. They had flown a group of officers from Italy to England while I was a prisoner of war. When leaving England their plane crashed on takeoff and exploded. Those killed included the pilot, First Lieutenant Eugene Thurman from Texas; co-pilot, Second Lieutenant George H. Jensen; the naviagator, Second Lieutenant Walter E. McKay; first engineer, Staff Sergeant Milton Hewitt of Kansas; and radio operator, Staff Sergeant Joseph C. Rosendale of Massachusetts.

Later I could get weekend passes (Friday night to Sunday night) to go home. I would take the train to Chicago and change to another to Clinton. The train went through Farmer City but did not stop there. I usually changed trains at 63rd Street station on the south side of Chicago. If I had time between trains I would call Richard Cox and he or someone else would meet me in Clinton. Sometimes I had to wait and call from Clinton. One time a railroad employee got off at Kankakee and called Richard so I wouldn't have to wait in Clinton. Because I was using crutches I always had a seat, although the train was usually full.

After coming home several weekends the doctor said I had to stay in bed and keep my leg elevated for two weeks before they would do surgery because my leg had not healed. The wound was all scar tissue except for an open spot right in the center about the size of a half dollar. The doctor needed to cut some more bone off so he could remove the scar tissue and get the skin pulled together to sew it up. He wanted to leave at least six inches of stump to permit use of an artificial leg. I think that is when I started smoking. I don't know why.

All the men in our room (10 or 12) had either one leg or one arm off and needed surgery. When someone was going to surgery our room had a routine. When they came to get them everyone would be real quiet and one man would play taps on the harmonica. He could really play taps. It would send chills down our backs. When they went through the door all of us would wish them well. Some of the hospital personnel thought it was cruel, but all of us had or would have the same treatment.

Often I would get in a wheelchair (an older wooden kind) with a tray and Tom Carter, who had an arm off, would push me to the commissary to buy milk shakes for who ever wanted them in our room. He couldn't carry a tray, and I couldn't walk. But together we could get the milk shakes. We usually brought one for the nurse in the doctor's office. One day after the doctor had told me to stay in bed we went after the shakes and took one to the doctor's office for the nurse. Instead of the nurse at the desk it was the doctor. Tom pushed me up to the desk. I didn't know what to say, so I just gave the doctor the milk shake and we got out of there. I was afraid he would recognize me and wonder why I wasn't in bed with my leg elevated. If he found out I had not been in bed for two weeks he might have postponed my surgery. This was the only time I ever saw the doctor in his office.

On Sunday before my surgery it was nice and warm so Tom took me out in the yard for a ride in a wheelchair. We didn't think the doctor would be at the hospital. We were on the sidewalk when another patient in a wheelchair started to pass us. So Tom started to race. The footrest on my wheelchair hit a raised place on the sidewalk and stopped. I landed several feet out in the yard. I wasn't hurt, but we decided to go back to the room before somebody got hurt.

The morning of May 8, 1945, I went to surgery to shape and finish the amputation started in Austria because my leg had not healed. Just before I left the room we heard the German Army had surrendered. I had a spinal shot so I talked to the doctor during the surgery. He started talking with me about the send-off our room gave to surgery patients. I told him we had discussed in the room what filing on a bone sounded like. We would run a file that we had been given to do craft work across the rail of our bed. We would tease a fellow about to go to surgery that when the doctor had to file on bone it would sound like us running a file across the iron bed rail. When the doctor started to file on mine he told me that that was what he was doing. And to my surprise it sounded like filing on metal. I still don't see how that was possible.

Remember, our room had only single amputees. For a short time they brought a double leg amputee into our room. One day during visiting hours several mothers were visiting other patients in the room. The double leg amputee asked another patient walking by to pick up something that had fallen off the foot of his bed out of reach. The guy turned to him and said, "You're not crippled. Get it yourself." And he did. The fellows would often help one another out. But this time the fellow was just teasing. The mothers were very upset by the remark. We became much more careful of what we said to each other when we had visitors.

The only therapy I had after my surgery before I got my artificial leg was to straighten my knee. Later I was moved out to a barracks at Fort Custer, Michigan. When my leg was healed I was fitted with a wooden artificial leg. I think it was in July. August 12 I was best man for Richard Cox and Joan (pronounced jo ANN) Parr's wedding. My Aunt Angeline Reynolds washed my summer uniform and put so much starch in it that it was white, and I couldn't wear it. At that time military personnel still on active duty were not allowed to wear civilian clothes until discharged. So I wore my winter uniform in August 1945 in Parr's farm house. When they threw rice on the wedding party I was so hot and sweaty that it stuck to me. Richard and Joan had waited to get married until I could walk on my artificial leg to stand up as best man.

On September 1, 1945, Richard and Joan Cox and I were walking past the bowling alley in Farmer City. Millie Stagen was home for the weekend from Chicago to help her mother celebrate her birthday. I saw Millie in there bowling. I went in and asked her if she would go to a movie with us. She did. After my discharge I made many trips to Chicago to see her.

Later, after I got home, I found out that the pilot and copilot were the only two killed when the plane I parachuted out of was shot down. I was discharged October 12, 1945, from Fort Custer, Michigan.

This has been an interesting experience and I don't regret any of it. I don't remember much about the pain except when the Germans were carrying me into the farm house and when the doctor replaced the drain. I started farming with Dad, Warren B. Holman, and Grandpa (Homer) Holman. Later I bought Grandpa's part of the machinery and livestock.

Mildred Stagen and I were married September 5, 1948. It was the best thing that ever happened to me.

The May 1997 edit was to add the information about Dean's five crew members who were killed while Dean was a prisoner of war (page 19). The July 1997 edit corrected the header to read WWII instead of WWI.

CLH

The website 376bg.org is NOT our site nor is it our endowment fund.

At the 2017 reunion, the board approved the donation of our archives to the Briscoe Center for American History, located on the University of Texas - Austin campus.

Also, the board approved a $5,000 donation to add to Ed Clendenin's $20,000 donation in the memory of his father. Together, these funds begin an endowment for the preservation of the 376 archives.

Donate directly to the 376 Endowment

To read about other endowment donation options, click here.

Reunion

NOTE change in the schedule !!

DATES: Sep 25-28, 2025

CITY:Rapid City, SD

HOTEL: Best Western Ramkota Conference Hotel; 2111 North LaCrosse St., Rapid City, SD 57702; 605-343-8500

Click here to view videos of the 2022, 2024, and 2025 reunions.

Click here to read about the reunion details.